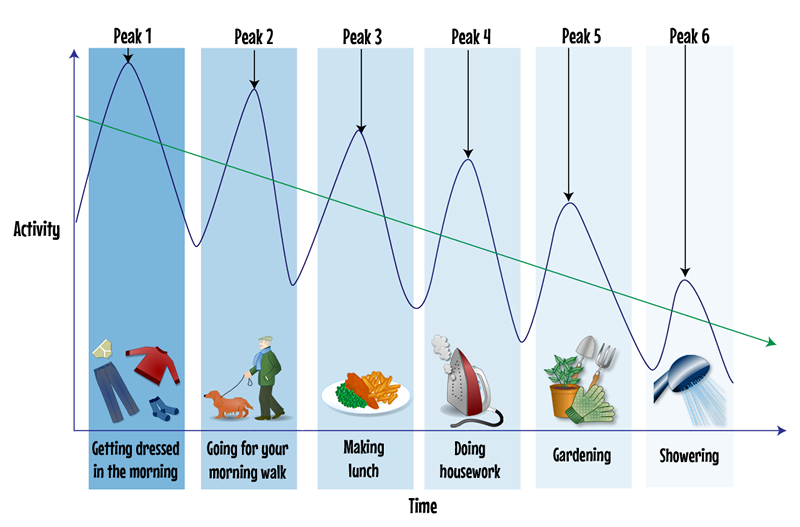

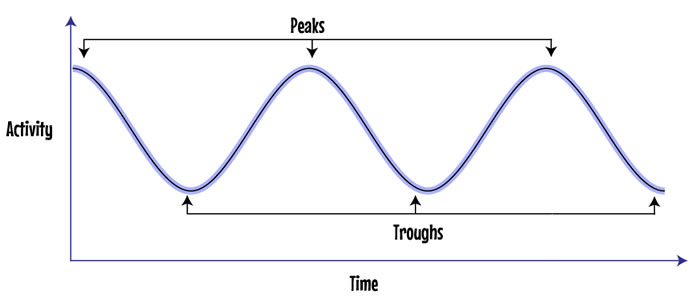

You can see that sometimes you are feeling well and can do a lot of tasks. Represented by the upward lines to each peak (over activity).

If you have done too much too soon you can run out of energy and the effort makes you tired and fatigued. This is represented by the downward lines to the trough (under activity).

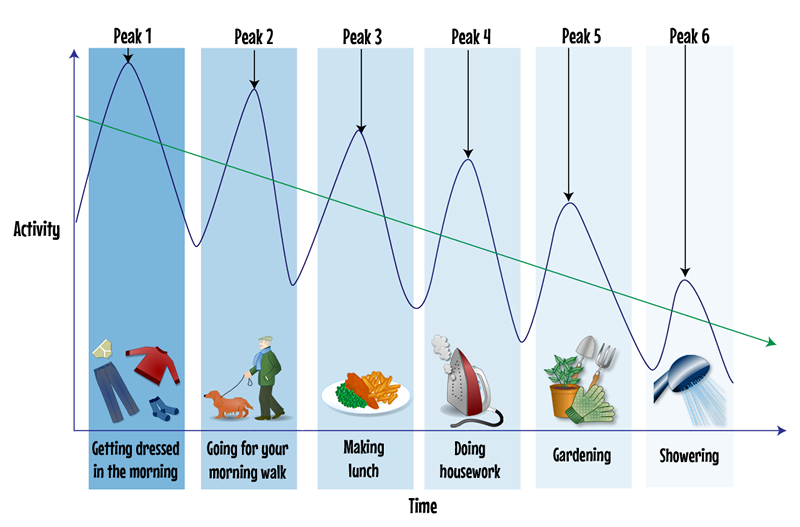

For example peak 1 is getting dressed in the morning. You rush to get ready to go out and energy drops in to the trough so you are forced to rest.

Peak 2 Is your morning walk. After a rest you feel better but you are behind schedule so you walk a little faster. You still feel fine until you start to get past your peak and energy drops in to the trough again, needing another rest. Your energy level does not get back to where it was earlier. You are gradually getting more fatigued.

Peak 3 Making lunch. By now you are feeling tired but need to keep going. You think if you do lunch quickly you can rest after. By the time you start to hit the next trough you feel too bad to enjoy the lunch you spent so much effort making.

This peak and trough goes on for the rest of the day until by peak and trough 6 you are finding short tasks are difficult when you have less energy left.

By learning to pace yourself you can reduce these peaks and troughs and use your energy in the best way. The is represented by straight arrowed line.

People like you living with COPD can experience these peaks and troughs at different times. For example you may feel low in the mornings until you have had your first medications and inhalers then feel better and stronger as the day goes on. Some people describe their own COPD as a roller coaster, especially after an exacerbation. This is when pacing can really help.

For more information on managing fatigue see page 36 :

Moving on Together (MoT): A self-management workbook by NHS Ayrshire & Arran.